By Art Reisman

CTO – http://www.netequalizer.com

Bandwidth providers are organized to sell bandwidth. In the face of bandwidth congestion, their fall back position is always to sell more bandwidth, never to slow consumption. Would a crack dealer send their clients to a treatment program?

For example, I have had hundreds of encounters with people at bandwidth resellers; all of our exchanges have been courteous and upbeat, and yet a vendor relationship rarely develops. Whether they are executives, account managers, or front-line technicians, the only time they call us is as a last resort to save an account, and for several good reasons.

1) It is much easier, conceptually, to sell a bandwidth upgrade rather than a piece of equipment.

2) Bandwidth contracts bring recurring revenue.

3) Providers can lock in a bandwidth contract, investors like contracts that guarantee revenue.

4) There is very little overhead to maintain a leased bandwidth line once up and running.

5) And as I eluded to before, would a crack dealer send a client to rehab?

6) Commercial bandwidth infrastructure costs have come down in the last several years.

7) Bandwidth upgrades are very often the most viable and easiest path to relieve a congested Internet connection.

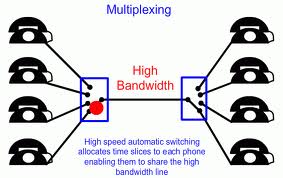

Bandwidth optimization companies exist because at some point customers realize they cannot outrun their consumption. Believe it or not, the limiting factor to Internet access speed is not always the pure cost of raw bandwidth, enterprise infrastructure can be the limiting factor. Switches, routers, cabling, access points and back-hauls all have a price tag to upgrade, and sometimes it is easier to scale back on frivolous consumption.

The ROI of optimization is something your provider may not want you know.

The next time you consider a bandwidth upgrade at the bequest of your provider, you might want to look into some simple ways to optimize your consumption. You may not be able to fully arrest your increased demand with an optimizer, but realistically you can slow growth rate from a typical unchecked 20 percent a year to a more manageable 5 percent a year. With an optimization solution in place, your doubling time for bandwidth demand can easily reduce down from about 3.5 years to 15 years, which translates to huge cost savings.

Note: Companies such as level 3 offer optimization solutions, but with all do respect, I doubt those business units are exciting stock holders with revenue. My guess is they are a break even proposition; however I’d be glad to eat crow if I am wrong, I am purely speculating. Sometimes companies are able to sell adjunct services at a nice profit.

Related NY times op-ed on bandwidth addiction

:

:

Will Bandwidth Shaping Ever Be Obsolete?

December 1, 2012 — netequalizerBy Art Reisman

CTO – www.netequalizer.com

I find public forums where universities openly share information about their bandwidth shaping policies an excellent source of information. Unlike commercial providers, these user groups have found technical collaboration is in their best interest, and they often openly discuss current trends in bandwidth control.

A recent university IT user group discussion thread kicked off with the following comment:

“We are in the process of trying to decide whether or not to upgrade or all together remove our packet shaper from our residence hall network. My network engineers are confident we can accomplish rate limiting/shaping through use of our core equipment, but I am not convinced removing the appliance will turn out well.”

Notice that he is not talking about removing rate limits completely, just backing off from an expensive extra piece of packet shaping equipment and using the simpler rate limits available on his router. The point of my reference to this discussion is not so much to discourse over the different approaches of rate limiting, but to emphasize, at this point in time, running wide-open without some sort of restriction is not even being considered.

Despite an 80 to 90 percent reduction in bulk bandwidth prices in the past few years, bandwidth is not quite yet cheap enough for an ISP to run wide-open. Will it ever be possible for an ISP to run wide-open without deliberately restricting their users?

The answer is not likely.

First of all, there seems to be no limit to the ways consumer devices and content providers will conspire to gobble bandwidth. The common assumption is that no matter what an ISP does to deliver higher speeds, consumer appetite will outstrip it.

Yes, an ISP can temporarily leap ahead of demand.

We do have a precedent from several years ago. In 2006, the University of Brighton in the UK was able to unplug our bandwidth shaper without issue. When I followed up with their IT director, he mentioned that their students’ total consumption was capped by the far end services of the Internet, and thus they did not hit their heads on the ceiling of the local pipes. Running without restriction, 10,000 students were not able to eat up their 1 gigabit pipe! I must caveat this experiment by saying that in the UK their university system had invested heavily in subsidized bandwidth and were far ahead of the average ISP curve for the times. Content services on the Internet for video were just not that widely used by students at the time. Such an experiment today would bring a pipe under a similar contention ratio to its knees in a few seconds. I suspect today one would need more or on the order of 15 to 25 gigabits to run wide open without contention-related problems.

It also seems that we are coming to the end of the line for bandwidth in the wireless world much more quickly than wired bandwidth.

It is unlikely consumers are going to carry cables around with their iPad’s and iPhones to plug into wall jacks any time soon. With the diminishing returns in investment for higher speeds on the wireless networks of the world, bandwidth control is the only way to keep order of some kind.

Lastly I do not expect bulk bandwidth prices to continue to fall at their present rate.

The last few years of falling prices are the result of a perfect storm of factors not likely to be repeated.

For these reasons, it is not likely that bandwidth control will be obsolete for at least another decade. I am sure we will be revisiting this issue in the next few years for an update.

Share this: