The video rental industry of the early 80’s was comprised of 1000’s of independent stores. Corner video rental shops were as numerous as today’s Starbucks. In the late 1990’s, consolidation took over. Blockbuster with its bright blue canopy lighting up the night sky swallowed them up like doggy treats. All the small retail outlets were gone. Blockbuster had changed everything, their economy of scale, and their chain store familiarity, had overrun the small operators.

In a similar fashion to the fledgling video rental industry, circa 1990’s Internet content was scattered across the spectrum of the web, ripe for consolidation. I can still remember all of the geeks at my office creating and hosting their own personal websites. They used primitive tools and their own public IP’s to weave these sites together. Movies and music were bootlegged, and shared across a network of underground file-sharing sites.

Although we do not have one Internet “Blockbuster” today, there has been major consolidation. Instead of all traffic coming from 100’s of thousands of personal or small niche content providers, most of it comes from the big content providers. Google, Amazon, Netflix, Facebook, Pinterest are all familiar names today.

So far I have reminisced about a nice bit of history, and I suspect you might be wondering how all of this prelude relates to tracking traffic by DNS?

Three years ago we added a DNS (domain name system) server lookup from our GUI interface, as more of a novelty than anything else. Tracking traffic by content was always a high priority for our customers, but most techniques had relied on a technology called “deep packet inspection” to identify traffic. This technology was costly, and ineffective on its best day, but it was the only way to chase down nefarious content such as P2P.

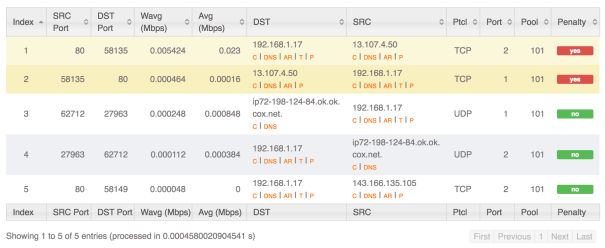

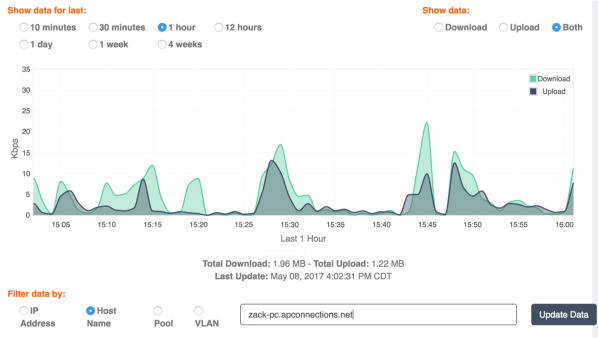

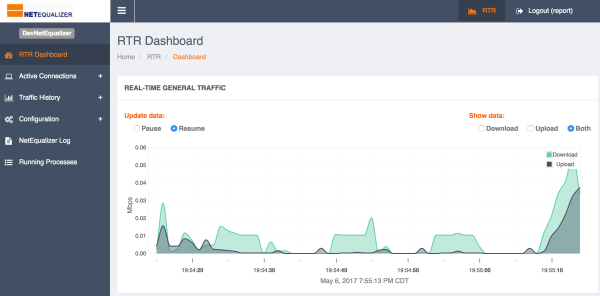

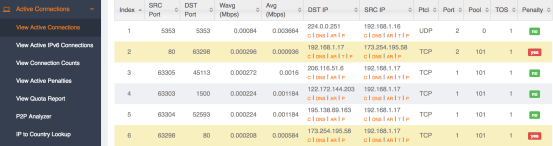

Over the last couple of years I noticed again the world had changed. With the consolidation of content from a small number of large providers, you could now count on some consistency in the domain from which it originated. I would often click on our DNS feature and notice a common name for my data. For example, my YouTube videos resolved to one or two DNS names, and I found the same to be true with my Facebook video. We realized that this consolidation might make DNS tracking useful for our customers, and so we have now put DNS tracking into our current NetEqualizer 8.5 release.

Another benefit of tracking by domain is the fact that most encrypted data will report a valid domain. This should help to identify traffic patterns on a network.

It will be interesting to get feedback on this feature as it hits the real world, stay tuned!

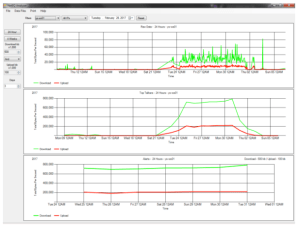

Once the IP’s were resolved to DNS names, I was surprised to see such high bandwidth from a specific PC. Bandwidth that was large and during closed office hours spreading across multiple days. I approached the user to see if they had any experience with slow or intermittent internet access and sure enough they did. Their experience of slowness was the NetEQ doing it’s wonderful job of penalizing them and normally it should, but the user experienced slowness due to a bug on the computer. They also stated they left their PC on overnight because they didn’t want to lose what they had been working on, so this explained why the traffic showed during closed hours. When asked if they knew when they started to experience slowness, their answer matched what the data showed in the four week report.

Once the IP’s were resolved to DNS names, I was surprised to see such high bandwidth from a specific PC. Bandwidth that was large and during closed office hours spreading across multiple days. I approached the user to see if they had any experience with slow or intermittent internet access and sure enough they did. Their experience of slowness was the NetEQ doing it’s wonderful job of penalizing them and normally it should, but the user experienced slowness due to a bug on the computer. They also stated they left their PC on overnight because they didn’t want to lose what they had been working on, so this explained why the traffic showed during closed hours. When asked if they knew when they started to experience slowness, their answer matched what the data showed in the four week report.

India IT a Limited Supply

June 30, 2017 — netequalizerBefore founding my current company, I was on the technical staff for a large telecom provider. In the early 1990’s about half of our tech team were hired on the H-1 visa’s from India, all very sharp and good engineers. As the tech economy heated up, the quality of our Engineers from India dropped off significantly, to the point where many were actually let go after trial periods, at a time when we desperately needed technical help.

The unlimited supply of offshore engineering talent evidently had its limits. To illustrate I share the following experience.

Around the year 2000, in the height of the tech boom, my manager, also from India, sent me on a recruiting trip to look for grad students at a US job fair hosted for UCLA students.

In my pre-trip briefing we went over a list of ten technology universities in India, as he handed me the list he said, “Don’t worry about a candidates technical ability, if they come from any one of these ten universities they are already vetted for competency, just make sure they have a good attitude, and can think out-of-the-box.”

He also said if they did not attend one of the 10 schools on the list then don’t even consider them, as there is a big drop off in talent at the second tier schools in India.

Upon some further conversations I learned that India’s top tech schools are on par with the best US undergrad engineering schools. In India there is extreme competition and vetting to get into these schools. The dirty little secret was that there were only a limited number of graduates from these universities. Initially, US companies were only seeing the cream of the Indian Education system. As the tech demand grew, the second tier engineers were well-enough trained to “talk the talk” in an interview, but in the real world they often did not have that extra gear to do demanding engineering work and so projects suffered.

In the following years, many US-based engineers in the trenches saw some of this incompetence and were able to convince their management to put a halt to offshoring R&D projects when the warning signs were evident. These companies seemed to be in the minority. Since many large companies treated their IT staff, and to some extent their R&D staff, like commodities, they continued to offshore based on lower costs and the false stereotype that these Indian companies could perform on par with their in-house R&D teams. The old adage you get what you pay for held true here once again.

This is not to say there were not some very successful cost savings made possible by Inidan engineers, but the companies that benefited were the ones that got in early and had strong local Indian management, like my boss, who knew the limits of Indian engineering resources.

Share this: